24 Aug A punitive Trump proposal stokes panic among immigrants — even before it’s official

California has been in the forefront of a pushback against a Trump administration draft proposal that could deny permanent residency or even citizenship to immigrants who have accessed public assistance programs or are expected to do so in the future. (Illustration by Edel Rodriguez for the Times)

“What if I get deported?” asked Kim, who immigrated to the United States from Korea nearly a decade ago and has a 21-month-old child with her husband, a U.S. citizen. “My baby and my family are here. What would happen to me?”

Kim, who spoke using a pseudonym, was explaining why she has not signed up for Medi-Cal, the California Medicaid program, even though she’s eligible. Her decision means she can’t get a mammogram because of the expense, even though doctors recommended an annual screening.

Kim’s fears aren’t unusual in California’s immigrant communities, even among naturalized citizens and lawful permanent residents (holders of “green cards”). The anxiety level spiked immediately after Trump was elected president on a platform including uncompromising hostility to immigrants. But over the last few months, a more specific concern has taken over, signified by a two-word shorthand: “Public charge.”

This will close the door to anyone except white, English-speaking, wealthy immigrants.

JACKIE VIMO, NATIONAL IMMIGRATION LAW CENTER

The term refers to a draft proposal by the Trump administration that could deny permanent residency or even citizenship to immigrants who have accessed public assistance programs or are expected to do so in the future. The plan’s implicit assumption is that immigrants are a burden on the public purse, so it’s better to weed out the costliest newcomers. But the assumption is a canard. A 2016 study by the National Academies showed that while first-generation immigrants are more costly to state and local governments than the native-born — mostly because of the cost of education — members of the second generation are “among the strongest economic and fiscal contributors in the U.S. population, contributing more in taxes than either their parents or the rest of the native-born population.”

Although public charge rules long have been part of the immigration and naturalization process, leaked versions of the proposal indicate that the administration intends a major tightening of the federal standards. Its aim appears to be to vastly expand the list of programs that would be counted against applicants for residency or citizenship.

In addition to cash assistance programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which is commonly described as “welfare,” it would weigh programs such as the earned income tax credit (EITC), the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), health plan subsidies under the Affordable Care Act and food stamps against applicants for the first time.

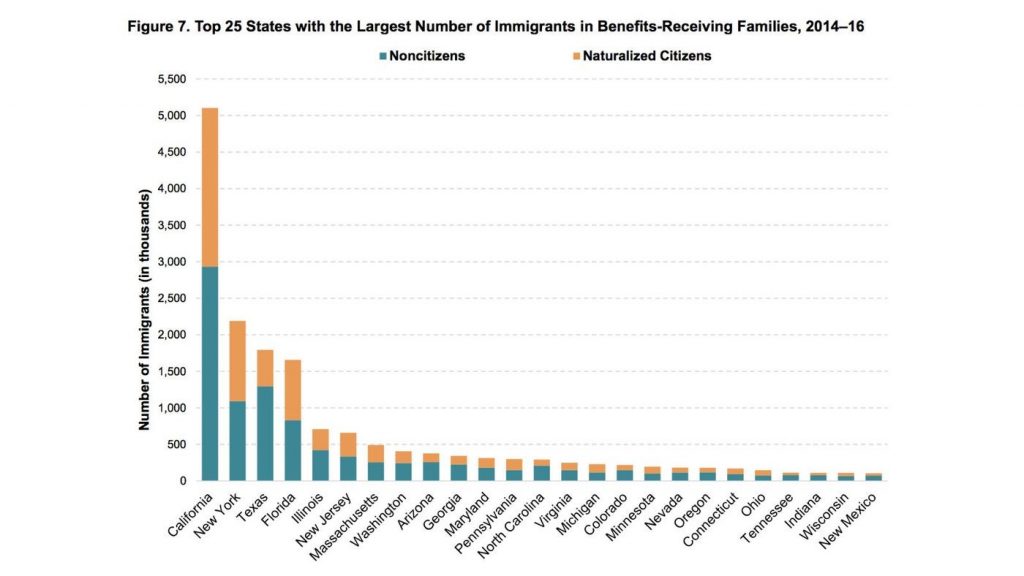

The change in policy would have a massive impact on California and Californians. The state is home to one-quarter of the 43.2 million foreign-born residents of the U.S., according to figures sent by Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra to Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney; half are naturalized citizens, and one-fourth each are legal permanent residents or undocumented. The 2 million California children enrolled in CHIP, a part of Medicaid, amount to 25% of all the program’s enrollees in the nation.

As a result, California has been in the forefront of a pushback against the proposal. On June 1, six representatives of Becerra’s office met in Washington with OMB officials to outline the potential economic impacts. They were joined in the room or by phone by representatives of Gov. Jerry Brown’s office and state health officials. Four San Francisco officials held a teleconference with the OMB on Aug. 13. Whether they received more than a polite brushoff isn’t clear — and won’t be until the final rule is published.

California’s public services are designed to be inclusive; the bars to immigrant access of healthcare and other programs are lower here than in many other states. “The leaked regulations would have an outsized effect on states which have reasonably generous eligibility, exactly like California,” Michael Fix, a senior fellow and former president of the Migration Policy Institute, told me.

Some clinics serving immigrant communities across California and nationwide say they’ve detected a marked dropoff in patients since earlier this year. That’s when rumors of the proposal intensified, following leaks of a policy draft submitted by the Department of Homeland Security to the OMB.

Patients eligible for Medi-Cal are shunning enrollment, figuring it would count against them in their applications. Others have simply stopped coming in for appointments. At Kheir Clinic, enrollments in Medi-Cal, Obamacare health plans, and My Health LA, a county program for low-income and uninsured residents, fell to 519 in July from 694 in March. Among the possible factors in the decline, the clinic believes that immigration policy issues play a role, according to Kirby Van Amburgh, its director of external affairs.

“The first sign for us is that our waiting rooms get empty,” says Isabel Cortez, operations director at Clinica Romero, which serves about 12,000 patients from two locations, including one on the edge of Boyle Heights across the street from Los Angeles County/USC Medical Center. Cortez estimates that monthly patient enrollments fell by about one-third after Trump’s election, and another 25% since the public-charge proposal leaked out.

The proposal hasn’t yet been formally published, and could differ significantly from the leaked drafts. But immigration advocates see the leaked versions as an attempt to rewrite immigration rules that were enacted by Congress in 1996.

“This is a radical proposal to do an end run around Congress,” says Jackie Vimo, policy analyst at the National Immigration Law Center in Washington. “This will close the door to anyone except white, English-speaking, wealthy immigrants.” That means abandoning the principle of inclusion on which America was built: If the same standards were in effect in the past, Vimo observes, “Most of us wouldn’t be here today.” The proposal is widely attributed to Stephen Miller, Trump’s hardline anti-immigration advisor.

This column is one of a series on the conflicts between California and the Trump administration. Feel free to send comments or ideas to Calvstrump@latimes.com.

Serving immigrant communities can be difficult under the best circumstances, whether they’re documented or not. With irregular living arrangements and wariness about official authority, they can be hard for doctors to reach or to keep on prescribed medication, sometimes because of its unaffordability.

Since Trump’s election, clinicians say, alarm has spread that immigration agents have been hanging around or trying to access personal information in the clinics’ files, or preparing to stage raids on the premises. The clinics have done their best to assuage their patients’ fears, but many still think it’s more prudent to stay away.

After Trump’s election, “So many patients came by just to say goodbye to their clinicians,” says Erin K. Pak, CEO of the Kheir Clinic. “They would tell us, ‘As a family, we decided we shouldn’t walk into any place but school and the grocery store.’”

“Subconsciously you always have fear,” says Maria (also a pseudonym), a patient at Clinica Romero. She emigrated from Mexico a few years ago, married an American citizen and has begun the application process for permanent residency. “To have access to healthcare, you have to show your address, your name and your phone number.”

A sufferer from diabetes, Maria hasn’t signed up for any public program that could count against her except for My Health LA. Clinics say they’ve been assured that enrollment in the program won’t show up on the federal radar screen; county health officials told me they’re “committed to safeguarding the privacy of patient personal information.”

The climate of heightened fear poses a quandary for doctors and clinics geared to serving immigrants. At both the Kheir Clinic and Clinica Romero, diabetes and hypertension are their top treatment concerns. Both require regular follow-up visits to be effectively managed and kept from turning into acute episodes of illness. That’s obviously a problem when patients turn into no-shows.

“If the patients are not following up,” Cortez says, “the next thing you hear is that they’re in the emergency room.”

The Trump administration has been vague about when it might formally submit the public-charge rule or what it will look like once it’s made final — conceivably because the ambiguity makes it harder for critics to mount a campaign to block it.

California far outstrips other states in the number of immigrants in families receiving public services. (Migration Policy Institute)

“The clinics are in a tough position, since it hasn’t happened yet,” Courtney Powers, director of government affairs at the Community Clinic Assn. of Los Angeles, told me. The latest rumor is that the rule will be submitted formally either just before Labor Day or within a few days after that.

All signs point to the administration’s intention to fast-track the measure. The leaked draft describes the rule as merely a “clarification” of existing policy. OMB, which has the final say on the rule, has attested that the proposal wouldn’t break the threshold of $100 million in annual impact that would make it “economically significant,” which would trigger a more detailed and public approval process.

The impact of a change in the public-charge definition could have an especially severe effect on mixed-status households — those comprising citizens and non-citizens, possibly including undocumented family members — because citizens and legal residents might steer clear of programs they’re eligible for in order to protect family members of lesser status. Those households aren’t uncommon: About half of California’s children have at least one immigrant parent.

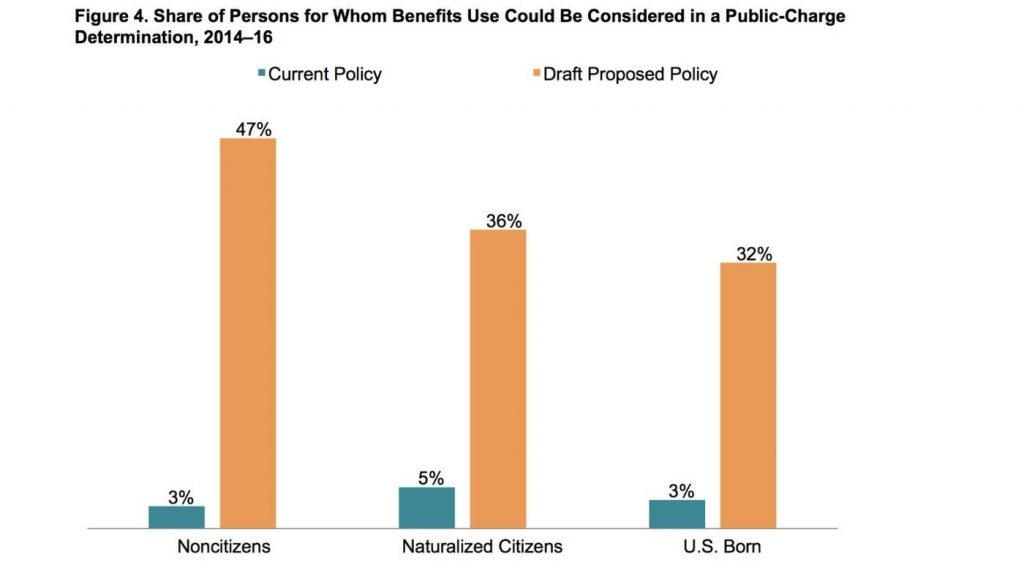

Drafts of the proposed new policy would drive the number of immigrants subject to public-charge assessment from 3% of noncitizens to 47%. (Migration Policy Institute)

The Department of Homeland Security currently applies the rule to those “primarily dependent” on the government, which it defines as obtaining more than 50% of income from cash programs such as welfare. When the rules were last codified in 1999, what was then the Immigration and Naturalization Service excluded non-cash programs from its calculation; its goal was to quell immigrants’ fears about using programs that enhanced public health or enabled them to find and keep jobs, such as transportation vouchers and child-care assistance.

In the most recent draft leaked publicly, Homeland Security suggests redefining the term to include “any government assistance” — not just 50% — from any means-tested program aimed at helping households meet needs for “housing, food, utilities, or medical care,” whether involving cash or not.

Under the existing regulations, Fix calculates, fewer than 3% of non-citizens living in the U.S. could have been designated public charges. The leaked proposal would increase that figure to 47%.

State and local officials and immigration experts consider OMB’s assertion that the proposal would have an economic impact of less than $100 million a year to be transparently absurd. San Francisco Mayor London Breed informed OMB Director Mulvaney in a July 19 letter that the cost in her city alone would come to between $129 million and $368 million in lost spending from food stamp benefits, Medi-Cal benefits, child-care subsidies and EITC income “due to families withdrawing from public supports … or not applying in the first place.”

Breed also pointed out the folly of raising obstacles to programs that serve a broad community purpose.

“This proposal,” she wrote, “will do irreparable harm to the productivity of our economy and compromise the health and safety of our communities.”

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Michael Hiltzik writes a daily blog appearing on latimes.com. His business column appears in print every Sunday, and occasionally on other days. As a member of the Los Angeles Times staff, he has been a financial and technology writer and a foreign correspondent. He is the author of six books, including “Dealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer Age” and “The New Deal: A Modern History.” Hiltzik and colleague Chuck Philips shared the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for articles exposing corruption in the entertainment industry.

[Source] LA Times by Michael Hiltzik